In 2019 a young man reported to his local polling place and cast his vote for his representative for the national legislature. It would appear to the outsider that he is clearly participating in the democratic process and surely he must appreciate the freedom he enjoys to control his government. However, in this case, he only had one choice to vote for. And that choice was selected not by a democratic process but by the Democratic Front for the Reunification of Korea. Worse, state police monitor the polling station to make sure everyone actually shows up. It is hard to look at this, the process of voting, and still consider it a demonstration of freedom.

Some may push back on this example though. For example, in the United States, candidates for office compete for the ability to run in an election through primaries. In this case, surely the people voting are “free”. It isn’t clear though that there is anything about democracy as a principal that ensures “freedom” for those participating in the act of voting. Democracy is actually a process for alignment between the preferences of some average person in a polity and the rules that are enforced by the government on that polity.

In previous forms of government there wasn’t necessarily any alignment between the ruling class and the people who were ruled. Even some of our early examples of the rise of democracy are really just an example when a ruler got into a disagreement with some of the other elites and was forced to make some concessions. It is hard to look at the Magna Carta and think it was anything more than a spat between two powerful groups, the King of England and the Barons he relied on for support. Was the Magna Carta really a declaration of human rights or an acknowledgement of the fact that practically the only rights we have are those we have the power to enforce. as Max Stirner said, “What you have the power to be you have the right to.”

Max Stirner was an anarchist though and I am not arguing for anarchism here. I am trying to understand what freedom is and what the implications are for people if democracy isn’t truly about freedom.

Let’s start with a simple definition of freedom. We say that freedom is the ability to act in accordance with your preferences. If acting in accordance with those preferences results in penalties being opposed on you by state power than we say you are less free. We don’t say that natural consequences of acting in accordance with your preferences is indicative of a lack of freedom. For example, if your preference is to cheat on your significant other they may find out and leave you. That is not an infringement on your freedom. If however, the state imposes penalties on you for infideltity; your freedom is being impinged.

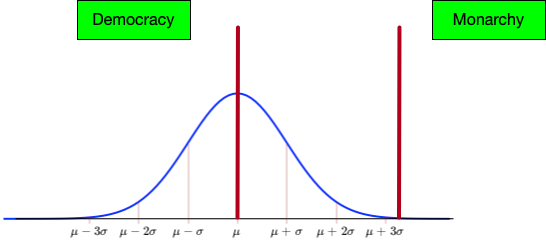

One way to visualize the difference than between previous forms of government like monarchy and today’s democracies and what the impact is on personal liberty is to consider a distribution of preferences in a population. In a monarchy the king or queen can set the law wherever they like. In that case we can measure the inverse of freedom as the average distance from the population’s preferred rules to the rules set by the monarch. In a pure democracy the rules will be set at the average preference of all people in a population.

Democracy simply aligns the laws of a society with the average of the preferences of society. The wider the distribution of preferences in this system the less freedom any individual will have. If the sets of preferences get disbursed enough people may decide that splitting into a different political group with their own legislature may make sense. In fact, when we look at a democracy through this lens we see that people are making several choices when participating in a democracy. First, they are sacrificing some level of personal freedom for the gains that come from being part of a larger group. Second, the more diverse a population is the bigger that sacrifice is and the tradeoff between the benefits of a large political entity and a split into smaller groups changes. Third, some people will try to leverage certain elements of society to move the laws away from being just an average of preferences. Some of these attempts will be systematic and in some cases could be to protect the rights of minority preferences. In other cases it will be more self-serving.

What kind of gains do people get for sacrificing some freedom for a government? In general we can think about two types of goods that someone could want. The first is a public good. By public good we don’t mean something that is provided by the government. We mean that the good is something that everyone can use at the same time and that no one can be excluded from using. Think about national defense. If a government pays for a military everyone in the country gets the benefits of having a strong military. Even if someone doesn’t pay their taxes they will still get the benefit of having a military protecting them from potentially hostile foreign countries. The fact that everyone gets the benefit of the military means that we can run into a free rider problem where enough people assume others will pay for the military and that they don’t have to. To get around this countries use governments to force people to pay taxes which are then funneled to national defense.

In the second case a good could be easy to exclude people from using it but because of the nature of the good it may make sense to provide the good from the government. In this case we would have a private good being paid for publicly. A good example where this could make sense is healthcare. Part of the reason health insurance doesn’t work well is that once you have a severe illness or injury an insurance company can predict with fairly high confidence that you will cost them more than you pay them in the future. Imagine you are diagnosed with a severe form of cancer but you recover and go into remission. Often you are at a much higher risk for hospitilization and death going forward. This dynamic provides an incentive for health care providers to cancel insurance on those with these conditions. Government supported health care bypasses this problem as everyone in the country contributes to healthcare as a pool.

The level of freedom a person has to sacrifice for either of these goods can be thought of as the distance from where their preferences are to the average of the population. If we assume that there is a link between freedom and fulfillment then the further you are from the average the less good democracy is for you. This has some implications when we think about the size and structure of countries and states. If you have a relatively homogenous population (think Scandinavia) then democracy in general will produce good results. People generally want the same things and the imposition of the average on people is not that high. In a more heterogenous society however there will be groups that feel the impact of having to live by the average’s preferences much more severely.

A good example of this second case is the United States. Often people making this point look to the large geographical size of the country. But the issue is far deeper in the United States. If you’re willing to use how a county votes (Republican or Democrat) in presidential elections as a proxy for preferences the differences jump out. Most cities in the US vote solidly blue while the more rural areas vote red. Considering that the left and right in the US have diverged in their core beliefs over the last twenty years we can explain much of the unrest and loss of faith in government on both sides of the political spectrum.

There are two traditional ways a group can handle heteregeneity in a population while trying to maintain a democracy. One is by codifying certain individual rights and then protecting those individual rights with certain institutions like a court system. We see this in the US where marriage equality was not driven by either the right or left wing (both had majorities in congress and controlled the presidency but refused to act on it) but rather by the Supreme Court stepping in to protect the rights of gay couples in America. The second way is through federalism. In the second case we try to maintain the benefits of a large country (a strong military for instance) while bypassing the issue of the average preference by allowing local governments as much authority as possible.

For several decades the idea of keeping decisions to local government was championed by the right wing in America while the left wing dismissed it as a ploy by racists to bypass the voting rights act. However, in more recent years the idea has gained traction on the left wing particularly around issues like immigration. This trend of wider, bipartisan acceptance of local government could be something that tones down some of the angry rhetoric in the US.

If we believe that living life according to our own preferences is a good then it is clear that we can’t just blindly assume that democracy gets us there. In fact, we have to take a much closer look outside of democracy to the institutions and systems that allow for differences in people throughout the country while protecting those with minority preferences. This challenge is more difficult the more diverse a population becomes but can lead to payoffs in a stable country that allows us to reap the rewards in security of a large country, while delivering the fulfillment that a small country provides.